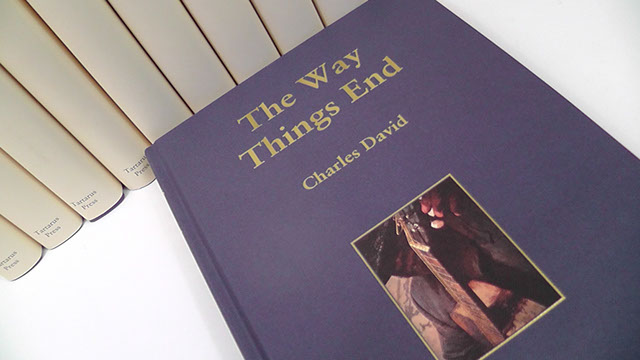

Review of: Charles David: “The Way Things End” (Tartarus Press, 2019)

Music is a unique carrier of mood. This is probably more true for the blues than for other genres of popular music. As Lightnin‘ Hopkins puts it: „Blues is a feeling.“ In contrast to many other popular music genres, Blues does not tell stories, it hardly knows any ballads, but works with repetition, wordplay, world-weariness and a good portion of humor. You could perhaps say that the Blues doesn’t tell stories but tells one big story. A murmuring tale of deportation, suffering, oppression, and the ability to keep a sense of humor in the midst of hardship.

This poses a challenge for literature. The Blues provides little basis for extensive narratives, although it does have a certain proximity to mythical, weird fiction. Blues lyrics often integrate elements of Afro-American folktales. Elements from hoodoo and (more rarely) voodoo, which today often remain known to us only through myth-making and perhaps not least the blues themselves: Who really knows anymore what a Mojo Hand is or a Black Cat Bone? Only the feeling that there is something deep, something mythical, seems as clear as the muddy waters of the Mississippi. Wasn’t there Robert Johnson? And didn’t he make a pact with the devil? Late at night at the crossroads? If you take a closer look, mysterious blues musicians offer material for many a tale – we’re thinking of „Southern Gods“ by J. H. Jacobs, for example – but it can easily turn out to be a problem. For example, when we find ourselves taking a romanticized look at a mysterious black culture whose depth is derived more from ignorance and stereotypes like the glorified ‚Magical Negro‘ than from a deep engagement with music and culture. Given that: How to write a novel about the Blues?

Blues for the End of the World

With his debut novel „The Way Things End“ Charles David explores one of these dirt roads. The first steps begin quite expectably. Set in 1940, at the time of the so-called Pre-War Blues, the black Blues musician Roosevelt ‚Rooster‘ Sands enters the literary and musical stage. The entry is hard and brutal. Sands kills Dab Wooley over money matters. But that plays less of a role in the rest of the story. As a music- or bluesman, Roosevelt simply continues his aimless journey, which is always accompanied by music. Lonely and with only a guitar and some superstition in his luggage, he travels restlessly through the country on foot or as a ‚hobo‘ in freight trains. Author Charles David uses these scenes to establish an atmosphere. The sequences of Roosevelt as a traveler, a ‚rambling man‘, are quite expected, but fit our idea of Blues musicians of that time well. At least that’s how we imagine the lives and travels of the aforementioned Johnson, Charley Patton, Lemon Jefferson and others. Violence, racism, alcohol, an undisguised view of the hard life, a good portion of mystery and above it all: Blues music as its expression. The folk legends are not to be missed either. In addition to the myth of Robert Johnson’s deal with the devil, David’s novel is about the fate of the number ’seven‘, sung among others by Willie Dixon and Muddy Waters.[1]

In this case, Sands is the seventh son of a seventh son, and that obviously doesn’t mean good luck, since his whole family burned to death in a fire. So he is left with only the Blues as a source of hope. Fed by his grief, the Blues flows effortlessly out of Sands: „The music came to him with ease, as if it had been waiting in him, as if it was wanting to be set loose from his mind and his fingers.“ (P. 22) The content of the song is also outlined by David in a rather stereotypical way, but with all expressive power. Roosevelt’s last song is the voice of the „lowliest of men, the most enraged and bent, the most tortured and misunderstood, a voice of suffering, the voice of all those who had felt pain or loss or separation, that was his song.” (P. 25) Hence, Blues functions as an expression of grief and an authentic truth that runs through Sands. And here the world ends and the Weird Fiction begins: „It was through Roosevelt Sands, on a red clay road under a nighttime sky somewhere deep in tobacco country in 1940, that the universe and all things within it began to unravel.” (P. 26) Roosevelt Sand’s story and song are only the prelude (and the end) of a narrative about the world falling apart. After the first chapter, the novel already leads us into completely different territory …

Refuge, Angels and a Whale in the Courtyard

And these territories have little to do with the Blues at first. Strictly speaking, it takes a full 16 chapters before the narrative comes back to Sands. Instead, we follow the compassionately told fate of Adelaide, a Jewish woman who is forced to hide from Nazi killing squads in a Romanian village and tries to forget her despair by writing stories. Or even the story of a giant rotting whale in a redneck’s courtyard in dusty Arizona. It’s a whole series of narratives that are often only connected at second and third sight. Occasionally we meet characters again in other times, or find unifying motifs such as glimpses of simple, troubled people. The real bond, however, lies in the music and an angelic vision that accompanies the disturbing sounds: „There was always music even when there was none.” (p. 11) It are the sad and pictorially described sounds of Roosevelt Sands that steadily accompany the end of the world and connect the fates that are far apart in time and space. Yet, this demands a lot from the reader.

Linguistically, David is brilliant. His phrasing is pointed and pictorial, even capturing the idiosyncrasies of dialects and eras. But this undoubtedly presents a challenge to non-native speakers. On the other hand, we have to make the connections between characters and narratives largely on our own. David gives us hints, clues and recurring motifs, but doesn’t make it too easy for us. That this is not due to a lack of craft, but is a deliberate effect, becomes clear from numerous meta-reflections. It is not by chance a quote from Baudrillard and not a line from a Blues song that prefaces the book and sets the tone. Or, as the blurb promises, it’s „A beautifully-written novel exploring the inter-connectedness of various disparate characters in the twentieth century …“ And that, after all, is something different than a story about the Blues.

Fragmented Chords

At the borders of the wholly interesting and vividly written story segments blur, crumble and splinter. Meaning itself is questioned, answered by music and then withheld again. One must want to engage in such a mental adventure to enjoy the book as a whole and not just its parts. The Blues tend to fall short in many chapters and unfortunately does not break out of some stereotypical conceptions despite proper research, although it is present in an indirect way in the sympathy for the simple, oppressed people. It takes some effort, however, to recognize this underlying pattern in the splinters of the book. But, as is well known, the splinter in the eye is probably the best magnifying glass …

[1] „Well now everybody cryin‘ ‘bout the seventh son; But in the whole round world there is only one, and; I’m the one, yes, I’m the one; I’m the one, I’m the one,; I’m the one they call the seventh son“ (Willie Dixon: The Seventh Son) And Muddy Waters sings: „On the seventh hours; On the seventh day; On the seventh month; The seven doctors said; He was born for good luck (Muddy Waters: I’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man). Waters‘ eldest son Larry „Mud“ Morganfield again takes up this motif in his song „Son of a Seventh Son“.

The Way Things End is available directly from the Publisher

This review was first published in German in Der Neue Stern #72 p. 21-24. I would like to thank editor Thomas Hofmann for allowing me to publish this translation. I wold also like to thank Tartarus Press for a digital review-copy of the book. Image of the book is used with friendly permission by Tartarus Press.

Also see the interview with Charles David on his book, that was conducted earlier this year for this blog: http://nighttrain.whitetrain.de/2021/08/05/blues-feels-like-a-struggle-to-me/