The Railroad in American Song

by Andreas Giesbert and Tobias Reckermann

The following article was originally published in Cthulhu Libria Neo 2: Horror in Eisenbahnen, a German magazine on speculative fiction with a focus on horror literature. It is presented here in translation with minor changes. The article is by no means a scholarly one, but rather the attempt to operate at the crossing between the tracks of music and literature. By following some junctions and crossings of those two forms of art, we hope to create a rickety bridge between readers of horror literature and fans of blues music. If we acquaint readers with names and tropes of early blues and folk music and give fans of the latter some reading recommendations, we succeeded in our task.

People have felt for a long time that when they die, someone should come and escort them into the afterlife. Some form of transition is probably found in every culture. Ancient Greece, with its idea of the river Styx as the border to the realm of the dead, over which the ferryman takes you in his barque; albeit at the cost of a few coins, the entrance does not come for free. There will be no return trip. In the Norse Edda, it is Valkyries, winged warrior women, who pick up the fallen from the battlefields. Since humans, even as the dead, are probably unable to fly, these stewardesses are needed to get to Valhalla. Thus, it can be stated that one does not find the way into the afterlife alone and not by one’s own strength.

In the course of history and technological progress, the form of the border as well as the ferryman changes, and so does the vehicle of passage. Roads already spread across the European continent and it is no longer only the crossroads where you meet the devil, but also the coachman who carries the deceased across with his horse and cart. Finally, industrialization knows its very own means of transportation, the railroad, and its incarnation of the ferryman, the conductor, and with it a new form of obolus for the ferryman. The conductor is not paid in cash. He is shown a ticket.

The railroad is a symbol of technological progress in the modern age, its network has been laid all over the world, its stations provide entry into a transportation system that spans the earth like blood vessels. Their function is particularly important in territorial states. The Trans-Siberian Railway, for example, covers a distance of more than nine thousand kilometers, which could hardly be considered economically passable without rail transport. Never could a modern commodity exchange have developed across this distance by the ancient means of caravans alone. The history of railroad construction in the USA, meanwhile, is deeply embedded in the frontier myth of the West.

More serious construction work began in 1865. It started in Omaha by the Union Pacific Railroad and in Sacramento by the Central Pacific Railroad.

It was at Promontory Summit on May 10, 1869, that Leland Stanford drove The Last Spike (or golden spike) that joined the rails of the transcontinental railroad. […] In perhaps the world’s first live mass-media event, the hammers and spike were wired to the telegraph line so that each hammer stroke would be heard as a click at telegraph stations nationwide (Wikipedia)

The great undertaking to connect both coasts with each other and thus an entire continent with itself had its price. The undertaking not only consumed enormous sums of money and reshaped entire stretches of land, but also burned up coal as well as the labor and often even the lives of innumerable wandering workers, consisting mainly of African Americans, marginalized Chinese and Irish, who performed hard labor for the construction under conditions that barely differed from the recently abolished slavery of the Southern states. Once the construction was completed, bison were conveniently „hunted“ from the moving trains, which contributed to their near extinction and derived the native peoples of North America of an important food source, which contributed to their genocide. Right from the outset, the railroad has had the smell of death all over it, which is arguably nowhere seen more symbolically than with the body of Abraham Lincoln, which was taken across the country on a train before being laid to rest for the last time. Trains would continue to serve as integral features of state ceremonies, engraving themselves into the collective American subconscious. Freedom Trains, decorated in blue, white and red, were a national political event, traveling through the United States as rolling museums displaying central documents associated with the formation of the state and the American myth. In the backward South, however, the Freedom Train was not welcomed enthusiastically, as the federal government insisted that citizens be allowed to visit the rolling museum regardless of the color of their skin. Questions of national division may have been quickly forgotten, however, when the visitors were rushed through the wagons under the guidance of military officers. They were allowed an average of three seconds per exhibit. Of course, the military was not only involved in train traffic to celebrate national identit

Railroads have been of great strategic importance in wars all over the world, since the wider world is accessible via rail networks. From the 1960s to the 1980s, for example, trains known as White Trains transported nuclear weapons across the United States.

[…] the United States began to transport their nuclear arsenal across the country in what were known as White Trains. These trains were white and heavily armed, complete with sniper turrets, armor and armed guards within. The white trains were made to be inconspicuous, moving nukes across the states to silos without attracting much attention.

The White Trains would be in operation until 1987 and run by the Department of Energy. While the trains were a national secret, kept hidden to avoid enemy spies from taking notice of weapons being transported, eventually, the citizenry of America took notice. With tensions and fears of nuclear war increasing, especially with the arrival of Ronald Reagan in the 80s, citizens began to speak out about nuclear proliferation. Anti-nuclear leagues began to protest and thousands took to the streets to fight the government’s war preparation policies. (Mysterious White Trains)

Nowadays, rail transport in the USA is in private hands and is gradually losing importance. Those who are used to the frequency of European train traffic will be surprised to learn that many American rail stations are only served twice a day and that air travel is not only the considerably faster mode of transport, but often also the cheaper one. Those who take the train enjoy the panorama and opt for the luxury option. Only for freight transport does the train continue to be of the utmost importance in the US.

These trends do not change the fact that the collective memory of the United States has embraced the train. And nowhere is this memory more clearly expressed than in folk, country and blues music, which serves as the voice and counter-voice of American consciousness and conscience. Whether it’s „Freight Train,“ „Hobo Blues,“ or the official song for „Freedom Train,“ trains are a recurring motif.

Songs about Trains

This song is a train song, it’s a song about a train (Freedom Train, Bing Crosby)

Providing a comprehensive overview of the train in folk songwriting is an almost impossible undertaking. A Wikipedia article on the subject lists more than a thousand songs alone, and doesn’t pretend to be exhaustive. Looking more closely at the song lyrics, some of them primarily praise the impressive technical power of the train:

Listen to the jingle, the rumble and the roar / As she glides along the woodlands, o’er the hills and by the shore / Hear the mighty rush of the engine, hear that lonesome Hobo squall / You’re travelling through the jungles on the Wabash Cannonball (The Wabash Cannonball, Carter Family)

More interesting, however, are the metaphorical aspects. We can loosely distinguish three interconnected themes: Freedom, Farewell, and Death.

Freedom

The hobo works and wanders, the tramp dreams and wanders, the bump drinks and wanders (unknown)

The fact that the U.S. government sent a Freedom Train through the country rather than a truck certainly had more than just pragmatic reasons. The train has always been associated with the idea of freedom. Being pulled through the vastness of America by such a powerful machine must undoubtedly be a liberating feeling. A freedom that was enjoyed not only by the paying guests, but also by numerous migrant workers driven by necessity. The hobo – a boy with a hoe – rides the train wherever blind spots – the blinds – allow him to elude the grasp of railroad guards (“the bulls”). The hobo is considered unbound, a Rambling Man who is here today and there tomorrow, leaving the city as he (or more rarely: she) wishes. In romanticized notions, it is as easily forgotten that this was due to the impoverishment of large parts of the population as a result of various economic crises as is the danger that accompanies such a trip. It is the poor who see the train as the last resort in the hope of finding work:

Let a poor man ride the blind / Said I wouldn’t mind it fellow / but you know this train / ain’t mine (Travelin‘ Blues, Blind Willie McTell)

The darker side of the hobo, or the bump and the tramp, has become a favorite subject of literature. James Vance and Dan E. Buer have set the Kings in Disguise (Kitchen Sink Press, 1990) a socially critical monument in the form of a graphic novel, and Lucius Shepard accompanied them in their life on the train – the Steel (Two Trains Running. Golden Gryphon Press, 2004). The hobo leaves society, becoming, as in Lucius Shepard’s story Over Yonder, part of a marginal society and an outside reality.

Farewell

Everyday nothing seems to change / Everywhere I go I keep seeing the same old things / And I can’t take it no more / I would leave this town / But I, I ain’t got no where else to go now / … / Gonna catch the next train / And I move on down the line / But I’ll be ready now / I’ll be ready when my train pulls in (When My Train Pulls In, Gary Clark Jr.)

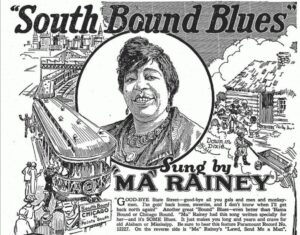

The mass migration to California triggered by the Great Depression of 1929 and by persistent droughts in the Midwest is closely linked to the image of the hobo, but it is not only migrant workers and hobos who are in constant motion. A relocation from the East to the West Coast (or vice versa) is a departure from a way of life, a confinement, an old love or an old self. Inscribed in the frontier myth is not merely the discovery and conquest of a territory, but first and foremost the leaving of an old world. A “We want to get out of here!” or an “I have to get out of here!” For those who stay behind, though, it is often a feeling of abandonment and mourning:

When the train rolled up to the station, and I looked her in the eye / Well, I was lonesome, I felt so lonesome, and I could not help but cry / All my love’s in vain / … / When the train, it left the station, with two lights on behind / Well, the blue light was my blues, and the red light was my mind (Love in Vain, Robert Johnson)

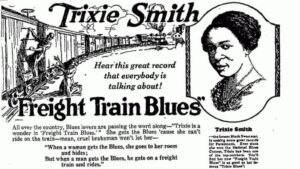

Freight trains could also be the occasion for comments on gender relations (song)

In the blues, this parting is often accompanied by the humor and optimism typical of the genre. The departing girlfriend can still be followed:

Well I’m gon‘ grab me a train, goin‘ back to Baltimore / I’m gonna find my baby, ‚cause she rode that B & O (B & O Blues No. 1, Blind Willie McTell)

When the bemoaned partner changes her mind, however, it is already too late, quite mundanely and without much romanticism, the male protagonist is no longer interested. After all he found „another hot mama“ in the meantime.

Freedom and farewell, an escape, a disappearance and departure into the unknown, however, already point to the aspect of death.

Death

There’s a little black train a-comin‘ / Comin‘ down the track / You gotta ride that little black train / But it ain’t a gonna bring you back (Little Black Train, Woody Guthrie)

The last passage connects itself even more explicitly with the train than the farewell, and it is precisely in this element that it also finds a connection to speculative fiction. At first, the train can be connected with death in a very material way, such as a means to suicide. Thus the lyrical I of the cynical-optimistic song „Trouble in Mind“ (composed by Richard M. Jones and recorded by Bertha „Chippie“ Hill, Big Bill Broonzy, Nina Simone and many more) knows that worries will only end, when he lays his head on the tracks of a lonely railroad track and the 2:19 train finally pacifies his mind.

Such a light-hearted, albeit tongue-in-cheek, thematization of suicide is perhaps only possible in the blues. But the train also has great significance in the quite contrary gospel music, which is nevertheless closely related to the blues. The train of the faithful does not transport sinners or gamblers (This Train is Bound for Glory) and the Staple Sisters even expect the „Gospel Train“ (Move Along Train). The train, however, is not only figuratively meant to keep its believers on the right track, but also often symbolizes death and the final farewell.

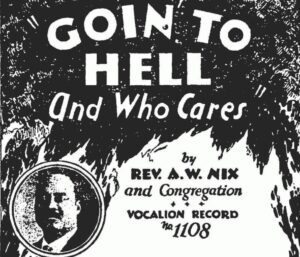

But of course, where Christian thinking prevails, the gate to hell is not far away:

There’s a long black train / Coming down the line / Feeding off the souls that are lost and crying / Rails of sin only evil remains / Watch out brother for that long black train (Long Black Train, Josh Turner)

Hellbound Train

Not only those who wander off the right track by mistake, but also those who willfully derail and turn to the mundane life can find themselves on a train headed for hell. An image that is no longer considered a warning in blues and rock, but can also be understood in an affirmative way:

Hellbound Train driving slow / Move on down to the Hell below / Conductor please won’t you lend a hand? / Got to get on board take me to your land (Hellbound Train, Savoy Brown)

Hell and the devil had a place in the blues from the very beginning and were euphorically taken up in the British folk & blues revival. The legend of Robert Johnson’s pact with the devil was taken up here just as readily and obsessively as Skip James‘ „Me and the Devil“. With its roughly hundred years of history, the blues has long since become a legend itself and lives its very own mythical life, in which truth and myth are creatively intertwined.

„That Hell-Bound Train,“ a short story by horror legend Robert Bloch, also adapted as a graphic novel by Joe R. Lansdale and David Wachter (Mercury Publications, 2011), combines the elements of a satanic conductor, a hell-bound train and a deal with the devil in the Dark Country of the American Midwest in a most prototypical way. Variations can be found in stories from Joe R. Lansdale (The Two-Bear Mambo, Mysterious Press, 1995) to Steven Spielberg’s 1985 episode „Ghost Train“ of the TV series Amazing Stories.

The American song, understood as a medium of narrative art, just like the horror novel, the short story or TV and cinema films, condenses recurring motifs around the train as a means of transport to the afterlife. Ghost trains travel throughout the country, and if you pay close attention, you can not only see them, but also get to hear them:

Hear that lonesome whistle callin‘ / On the barren desert fallin‘ / Loud and clear, just hear that lonesome wail / But it’s just the ghost, the phantom of the rail (Ghost Train, Marty Robbins)

Illustrations in this article are taken from historical advertisements. We would like to thank document records for collecting and sharing them on social media.